A STUDY OF PAY AT THE WASHINGTON POST

Washington Post employees work hard every day to ensure that our company is a leader in the journalism industry. Members of our company’s union, The Washington Post Newspaper Guild, believe The Post should also lead the way in how it treats its staff.

(Download this report as a PDF)

We want to foster an environment where all people, regardless of their gender, race, religion, sex, age or job, feel they are heard, respected and paid fairly.

Our company has expressed a commitment to these values. But the members of the Post Guild believe that true progress can only be achieved when we begin with the facts. And the facts tell us that The Post has a problem with pay disparity.

The Post has never conducted and released to the public a comprehensive pay study of its own. So this year, Post Guild decided to do one itself.

Our union contract with Post management mandates that the company give us pay data on Guild-covered employees on an annual basis. We requested this information in July 2019 and spent four months analyzing the data, a reporting effort led by Pulitzer Prize-winning data journalist Steven Rich and supported by a team of dozens of other Post Guild members. We took care to protect the integrity of the data and the privacy of our members.

The result of those efforts is this new report — the most comprehensive study to date of pay at The Washington Post.

This is what we found.

IN THE NEWSROOM:

- Women as a group are paid less than men.

- Collectively, employees of color are paid less than white men, even when controlling for age and job description. White women are paid about the median for their age.

- Women of color in the newsroom receive $30,000 less than white men — a gap of 35 percent when comparing median salaries.

- The pay disparity between men and women is most pronounced among journalists under the age of 40: When adjusting for similar age groups, which in most cases is a good stand-in for years in journalism, it becomes clear that the pay disparity between men and women exists almost exclusively among employees under the age of 40.

- Men receive a higher percentage of merit pay raises than women, despite accounting for a smaller proportion of the newsroom.

- The Post tends to give merit raises based on performance evaluation scores, but those who score the highest are overwhelmingly white. The Post is fairly consistent across races/ethnicities and genders at awarding raises to those who do well on performance evaluations.

- But in 85 percent of instances in which a 4 or higher was awarded to a salaried newsroom employee, that employee was white. Employees are rated on a scale of 1 to 5.

- On the flip side, 37 percent of scores below 3 were given to employees of color in the newsroom (the newsroom is about 24 percent nonwhite).

- Pay disparities have narrowed from the Graham era to the Bezos era, but most have not shrunk to within what could be considered parity.

IN THE COMMERCIAL DIVISION:

- Men and women are paid about the same. Gender pay disparities are nearly nonexistent among salaried employees in the commercial division’s nine departments.

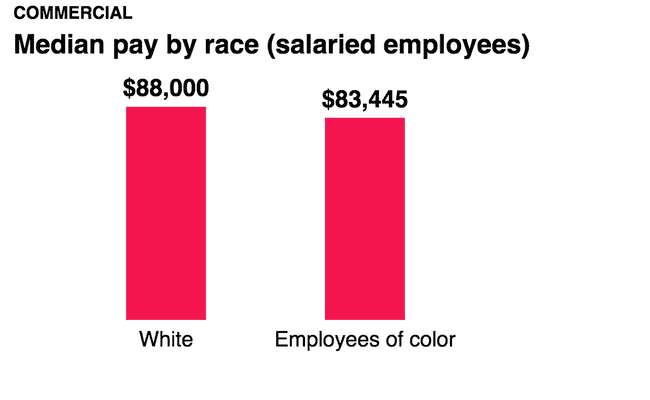

- Pay disparities do exist, however, when analyzing for race or ethnicity. The median salary for white employees in commercial is $88,000, compared with $83,445 for people of color — a difference of $4,555, or 5 percent.

- The disparity is even larger when adjusted for age, suggesting that employees of color in commercial are paid less than their white peers despite having more experience.

The Guild recognizes that these are complicated problems and reflect deeply entrenched disparities in our society. But we believe the company can and must make a significant and urgent effort to address them.

The results of the study were shared with the company ahead of publication. Members of the Guild also met with representatives of Post management to review the findings and invited management to respond. The company declined to comment. If The Post disagrees with any of the Guild’s conclusions, we welcome the company to conduct and share a study of its own.

We must note that the ability to analyze pay disparities at The Post has been hindered by the company’s lack of specific data on the professional experience of its employees, who sometimes have built lengthy careers before joining The Post. The relative lack of diversity at The Post, particularly the relatively low numbers of black and Hispanic or Latino newsroom employees, also complicated our analysis because of the small sample sizes — but in itself demonstrates that the company must do better to recruit and retain a diverse staff.

We know there are common-sense steps the company can take to eliminate these disparities, and we have outlined a list of those recommendations at the end of this report.

We believe in The Washington Post's ability to do better. We want to help our company get there. This is our guide to making it happen.

THE POST’S WORKFORCE

Among all current Guild-covered employees, about two-thirds (707 in total) are salaried. Among those employees, the mean salary is $112,383, while the median salary is $99,904. The median salary is generally a better metric for salaries. The higher mean suggests that the highest salaries have skewed the average upward.

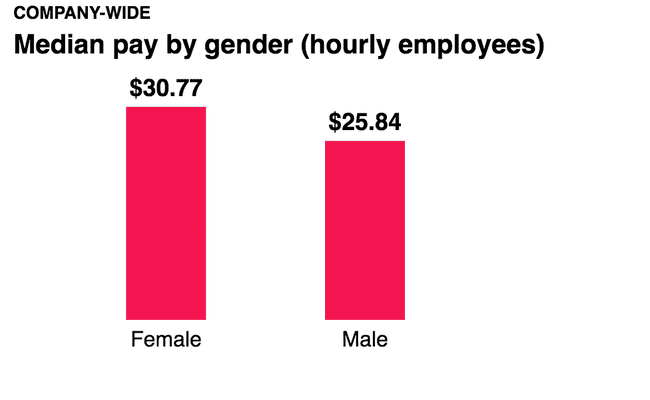

The other third of employees (243 in total) are hourly. The median hourly rate for those employees is $29.23 an hour. While this study will largely focus on salaried employees, some sections will analyze hourly employees. The data does not have a field for hours worked per week or average hours worked per week, so take-home pay is difficult to discern — a major difficulty encountered in this study.

Conducting a pay study of an organization like The Washington Post is not easy. Because the organization isn’t flat, meaning not everyone with the same amount of experience is working the same job, topline numbers such as median salary by gender or race and ethnicity cannot capture the entire story of pay at The Post. Those figures presented here should be understood primarily as a starting point for discussion. Ultimately, the goal in this report is to add nuance to this analysis, and demonstrate truer metrics for pay at The Post, accurately capturing the landscape to determine where the organization has genuine pay parity, and where it has disparities.

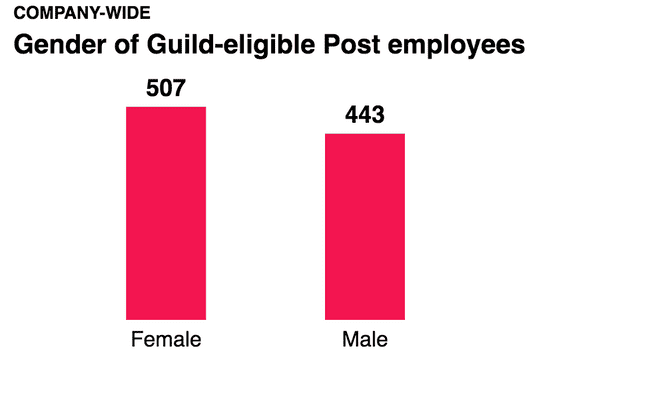

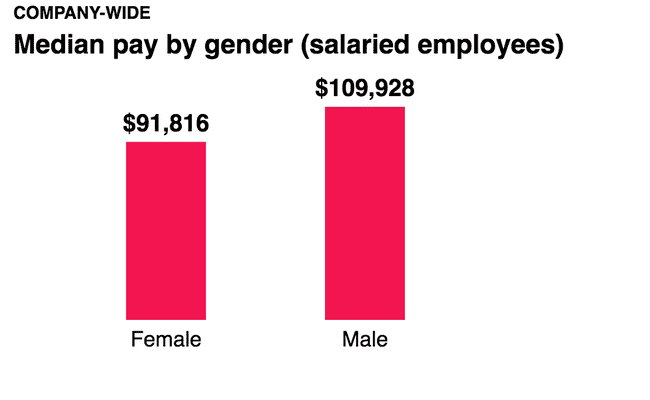

Of all current employees, 53.4 percent are female and 46.6 percent are male. Among salaried employees, 52.3 percent are female and 47.7 percent are male. The median salary for the 337 salaried male employees at The Post is about 20 percent higher than the median salary for the 370 salaried female employees: $109,928 compared with $91,816. One potential reason for some of the $18,000 disparity is the median age of each gender. For men, the median age is 41, while the median age of women is 35.

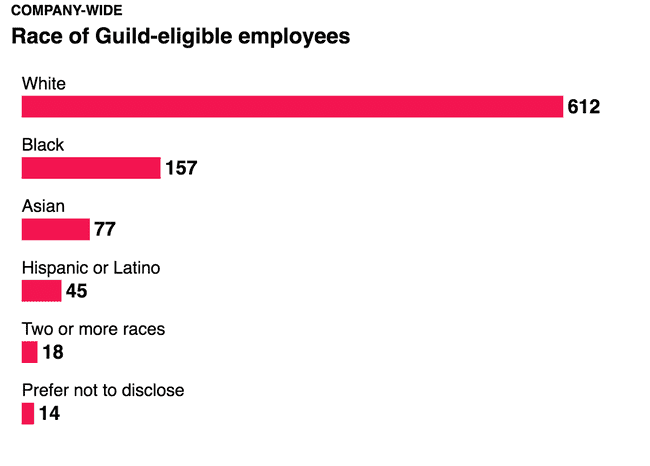

To study employees by race and ethnicity, the Guild again relied on information provided by management, which means the provenance of the data was unclear. The information on race and ethnicity was combined into just one field, which prevented the Guild from separating the two for analysis. Not every employee has a race or ethnicity listed, but the vast majority do. Only 22 current employees, just over 2 percent, do not have this information listed in the database.

Of 950 current employees, the racial and ethnic breakdown is as follows:

- White employees: 64.4 percent

- Black employees: 16.5 percent

- Asian employees: 8.1 percent

- Hispanic or Latino employees: 4.7 percent

- Employees with two or more races: 1.9 percent

For the 707 salaried employees, the racial and ethnic breakdown is as follows:

- White employees: 71.4 percent

- Black employees: 8.8 percent

- Asian employees: 8.3 percent

- Hispanic or Latino employees: 4.7 percent

- Employees with two or more races: 2 percent

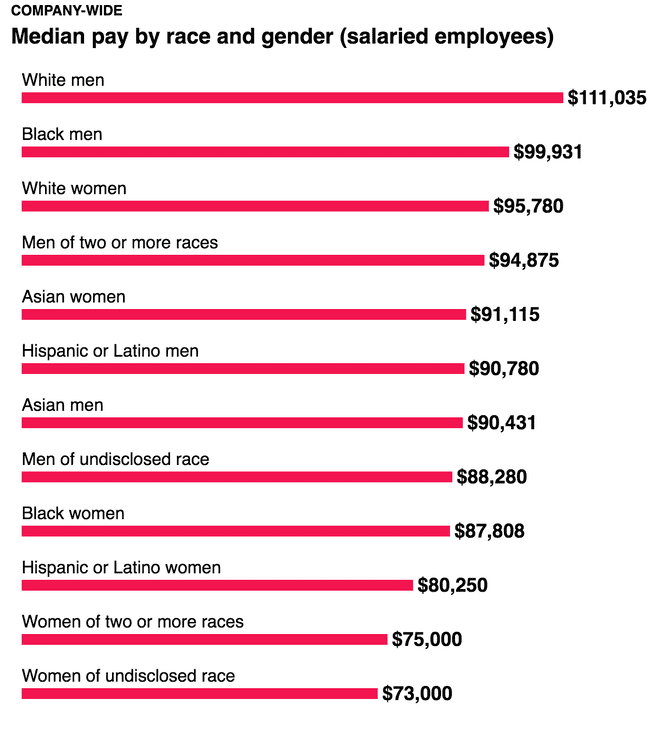

The median salary by race and ethnicity for those salaried employees is as follows:

- White employees: $102,880

- Black employees: $91,881

- Asian employees: $90,780

- Hispanic or Latino employees: $82,000

- Employees with two or more races: $79,860

NEWSROOM

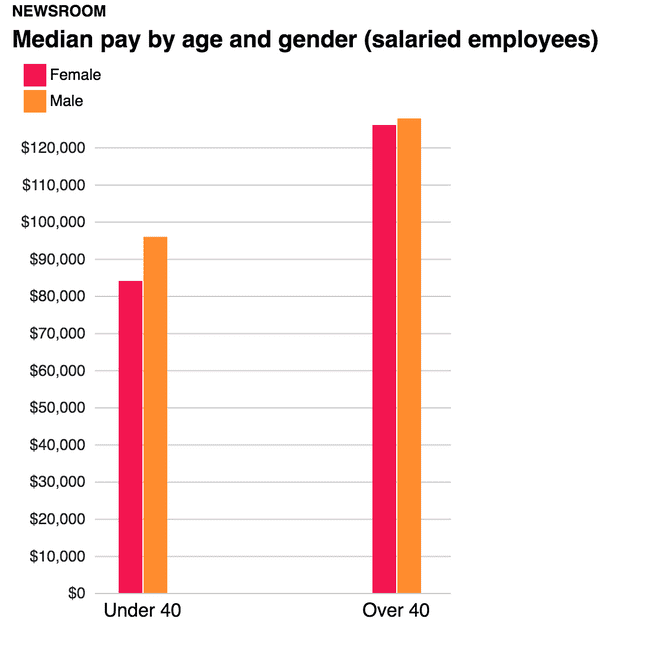

For the 290 salaried male newsroom employees working at The Post, the median salary is $116,065. For the 284 salaried female newsroom employees, it is $95,595. These groups have disparities in age and years of service: The median age for men working in the newsroom is 41, compared with 35 for women.

When adjusting for similar age groups, which in most cases is the best stand-in for years of experience in journalism included in the data, it becomes clear that the pay disparity between men and women exists almost exclusively among employees under the age of 40. For men and women 40 and over, the median salaries are separated by less than 1.5 percent: $127,765 compared to $126,000, respectively.

For men and women under the age of 40, the gap is more than 14 percent, with the median salary for men at $95,890, compared to $84,030 for women. It’s unclear why this topline disparity exists only for this age bracket. One possible explanation is a hiring disparity in positions that The Post considers more prestigious, and therefore higher-paying. Another explanation might be the pay disparities across races and ethnicities: The younger women at the organization are more diverse.

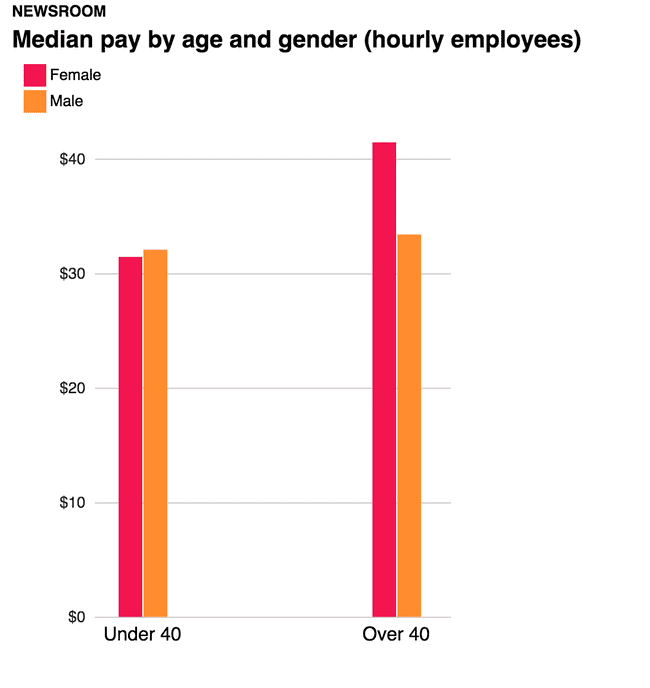

For 96 hourly employees across the newsroom, there is virtual pay equity. The median hourly wage for men is $33.33, compared with $32.75 for women. Comparing by age is difficult because only 33 men work hourly jobs in the newsroom and their ages vary widely. That said, there is virtual pay parity between male and female hourly workers under the age of 40. Women make more money than men working hourly over 40, but the sample size for men is low (15), meaning a few employees can lower or raise the median fairly drastically.

In the newsroom, 71 percent of salaried Guild-eligible employees are white and 24 percent of employees are nonwhite. Below are the median salaries by race and ethnicity across the newsroom:

- White: $106,212

- Black: $97,276

- Asian: $95,205

- Hispanic or Latino: $82,890

- Two or more races: $79,860

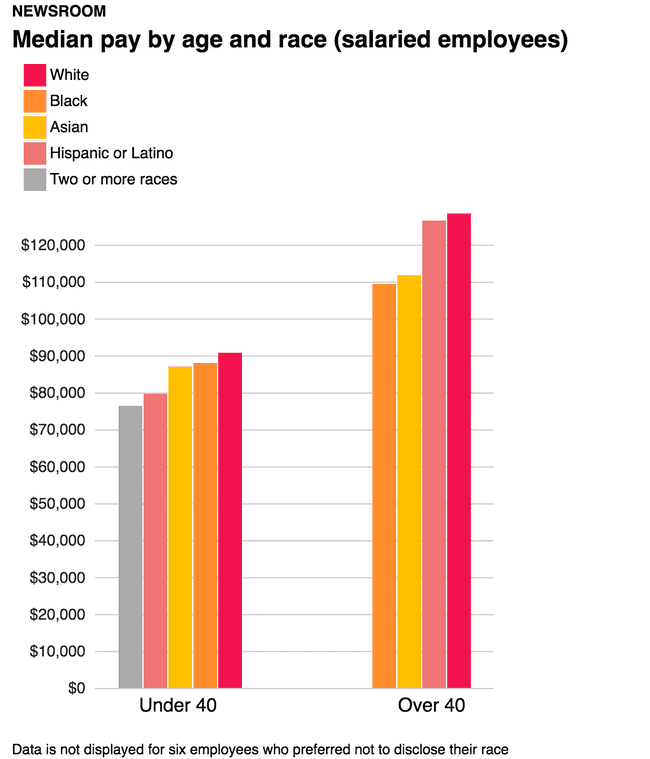

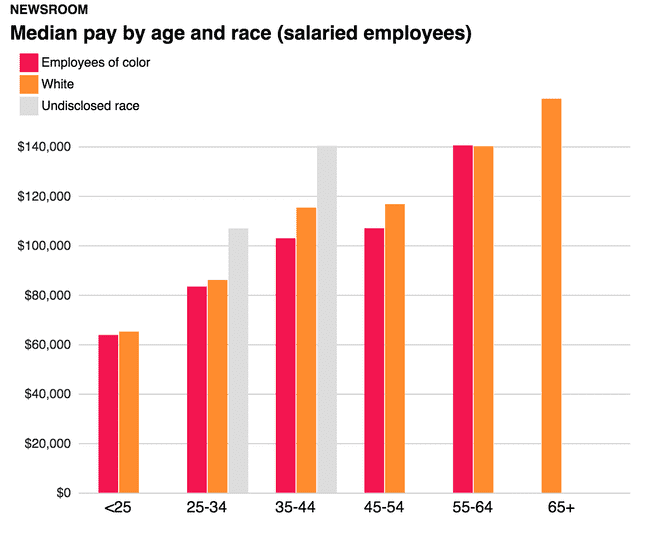

The total gap between white journalists in the newsroom and journalists of color is more than 15 percent, with a median salary of $106,212 for 406 white journalists and $92,080 for 139 journalists of color. Much like the gender gap, some of this could be explained by age and years of service: White journalists have a median age of 40 and journalists of color have a median age of 36.

But age doesn’t explain everything. Young employees of color across the newsroom don’t have complete parity with their young white colleagues. Among those under 40, newsroom employees of color make about 7 percent less than white journalists, with median salaries of $84,780 and $90,780, respectively. The disparity widens for journalists 40 and over: Newsroom employees of color have a median salary of $110,845, while their white colleagues have a median salary of $128,484 — a gap of nearly 16 percent.

About two-thirds of hourly employees in the newsroom are white, making this category more diverse than salaried workers. However, a racial pay gap still exists among hourly employees, with white hourly employees making a median wage of $33.59 an hour, compared to $30.07 for hourly employees of color. That gap of 11.7 percent is well outside the range that the Guild would consider parity in pay. When accounting for age, gaps still exist, though the analysis is difficult because there are only 30 hourly employees of color in the newsroom.

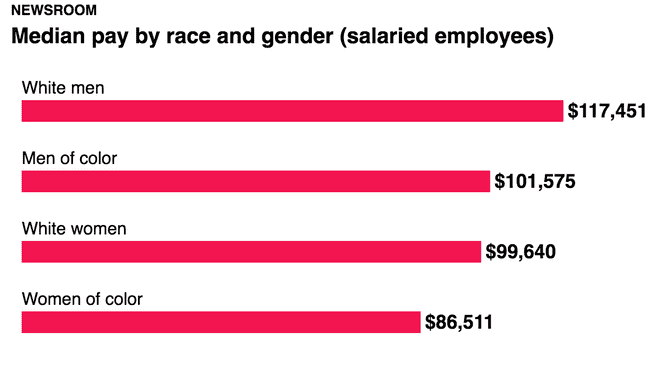

We would be remiss if this study did not examine gender, race and ethnicity through an intersectional lens. Across most industries, disparities increase when multiple factors are taken into account. Our analysis shows a similar pattern. The median salaries by group are as follows:

- White men: $117,452

- Men of color: $101,575

- White women: $99,640

- Women of color: $86,511

The gender pay gap is fairly similar across races and ethnicities. White men make about 18 percent more than white women, and men of color make 17 percent more than women of color across the newsroom. Likewise, racial pay gaps are similar across genders, with white men making about 16 percent more than men of color and white women making 15 percent more than women of color.

When comparing white men in the newsroom to women of color in the newsroom, the gap is over 35 percent, with the median salaries separated by more than $30,000. Here, again, some of this may be attributed to the fact that white men working at The Post have the oldest median age of any group across the newsroom. Median ages by group are as follows:

- White men: 41

- Men of color: 40

- White women: 37

- Women of color: 33

Controlling for age does, in fact, close the gap significantly between white men and men of color and also between white women and women of color. The gender gaps remain fairly consistent.

The Guild attempted to determine median salary by age group as a way to analyze pay by gender and race and ethnicity, and to determine which groups were paid above and below those benchmarks when age disparities were corrected. Controlling for age, here is how the median salaries for the four groups stack up:

- White men are paid an average of 7.27 percent higher than the median for their age group

- Men of color are paid an average of 1.73 percent lower than the median for their age group

- White women are paid an average of 0.14 percent higher than the median for their age group

- Women of color are paid an average of 3.26 percent lower than the median for their age group

Based on this analysis, The Post underpays men and women of color relative to white men. It pays white women about the median for their age.

One unexplored detail in this analysis is how desks factor into the equation: Do disparities exist within desks, and if they do, to what degree? For this, the Guild grouped cost centers into desks where appropriate. But many desks are not captured in the analysis because they are too small to evaluate.

In general, we found the same pattern of disparities throughout the newsroom, but also discovered that desks with some of the highest median salaries — such as National, Financial and Investigative — also had higher percentages of white men. This suggests that The Post must do more to cultivate women and people of color for those desks that demand the highest levels of skill and experience and therefore command the highest salaries.

Of 14 desks that have at least five men and five women, the median pay for men is at least 5 percent higher on 10 desks. Two have a median pay disparity that favors women by at least 5 percent, and two have approximate pay equity between the genders (within 5 percent).

Of 10 desks for which there were at least five white journalists and five journalists of color, seven desks have a median pay disparity favoring white journalists by at least 5 percent. Zero have a median pay disparity favoring journalists of color by at least 5 percent, and three have approximate pay equity between the two (within 5 percent).

There are only three desks that have at least five white men, five white women, five men of color and five women of color: National, Local and Design. All three have racial and gender pay disparities. Of those three desks, all have disparities in median salary of more than 30 percent between white men and women of color.

One prominent factor for these pay disparities is that the higher the median salary is for a desk, the higher its percentage of journalists who are male and the higher percentage of journalists who are white.

For desks in which the median salary is higher than $125,000, 80 percent of journalists are white and 57 percent of journalists are men. Those desks include National, Financial and Investigative. In this group, 47 percent of journalists are white men and 10 percent are women of color. For desks in which the median salary is below $92,000, 68 percent of journalists are white and 40 percent of journalists are men. In this group, 28 percent of journalists are white men and 21 percent are women of color.

In an equitable pay environment, one would expect that 50 percent of people in each group would be above the median salary and that 50 percent would be below. Controlling for age and median desk salary, the following represents how many employees are above the median expected salary:

- White men: 57.6 percent

- White women: 48.9 percent

- Men of color: 41.2 percent

- Women of color: 38.5 percent

The deviation from the median for each of these groups when controlling for age and median desk salary is as follows:

- The median salaried white male employee makes $2,448 a year more than the expected median salary for their age and assignment

- The median salaried white female employee makes $14 a year less than the expected median salary for their age and assignment

- The median salaried male employee of color makes $407 a year less than the expected median salary for their age and assignment

- The median salaried female employee of color makes $1,360 a year less than the expected median salary for their age and assignment

We recognize that these groups aren’t monoliths, and so in a normal distribution of pay, the Guild would expect about a third of employees to make within 5 percent of the median for their age and desk, about a third to make more than 5 percent below and about a third to make more than 5 percent above. Those distributions also show disparities among these groups.

- White men: 32.4 percent of employees make more than 5 percent below the expected median salary and 48.1 percent make more than 5 percent above the expected median salary

- White women: 38 percent of employees make more than 5 percent below the expected median salary and 35.3 percent make more than 5 percent above the expected median salary

- Men of color: 41.2 percent of employees make more than 5 percent below the expected median salary and 29.4 percent make more than 5 percent above the expected median salary

- Women of color: 46.2 percent of employees make more than 5 percent below the expected median salary and 25.6 percent make more than 5 percent above the expected median salary

The data also shed light on who received raises over the past five years and their performance evaluation scores for the past four.

For men and women in the newsroom, the median performance evaluation score is even, at 3.4 for 3,664 evaluations conducted over four years. Analyzed by race and ethnicity, scores started to diverge. Among groups for whom more than 20 evaluations were done over the four years from 2015 through 2018, the median performance ratings were as follows:

- White: 3.5

- Asian: 3.4

- Hispanic or Latino: 3.3

- Black: 3.3

- Two or more races: 3.2

For men, performance ratings were always at least equal to those of their female counterparts of the same race or ethnicity. Ratings for men and women by race and ethnicity were as follows:

- White men: 3.5

- White women: 3.4

- Asian men and women: 3.4

- Hispanic or Latino men and women: 3.3

- Black men: 3.3

- Black Women: 3.25

- Men and women of two or more races: 3.2

It is unclear what accounts for these disparities in performance evaluation scores.

Most pay raises in the newsroom are a result of Guild-negotiated contracts that award across-the-board increases in salaries. In addition, people also receive merit pay increases, which are based on performance evaluations and awarded solely at the discretion of management. Merit pay increases account for 26 percent of all raises. They are an important way to reward effort and initiative but can also create and magnify disparities if the company does not take steps to ensure fairness in the way performances are evaluated and rewarded.

Men received 51.7 percent of those merit raises, and women received 48.3 percent. (The newsroom’s gender makeup is 48.2 percent men and 51.8 percent women.)

The percentages of merit raises distributed by race and ethnicity for salaried journalists are as follows:

- White: 75.7 percent

- Black: 9.3 percent

- Asian: 8.3 percent

- Hispanic or Latino: 3.6 percent

- All others: 3.1 percent

For contrast, over that time the racial and ethnic makeup of salaried employees is as follows:

- White: 70.1 percent

- Black: 9.1 percent

- Asian: 8.5 percent

- Hispanic or Latino: 4.6 percent

- All others: 7.7 percent

The Post contends that merit raises are tied mostly to performance evaluations, and the data bears that out. Those who score higher, regardless of race, ethnicity or gender, tend to be the ones who get merit raises most frequently. However, an analysis of every performance evaluation score over the past four years shows that those who score the highest are overwhelmingly white. In cases in which a 4 or higher was awarded to a salaried newsroom employee, 85 percent were white, and over half of scores of 4 or higher were awarded to white men. And in cases in which salaried newsroom employees were given a score of 3 or below, 37 percent of those scores were given to employees of color (the newsroom is about 24 percent nonwhite).

GRAHAM FAMILY ERA VS. BEZOS ERA

Finally, the Guild wanted to examine whether pay disparities had changed after Amazon founder Jeff Bezos bought The Washington Post in 2013 from the Graham family. Analysis shows that from the Graham era to the Bezos era, pay disparities have shrunk slightly, but not to within a range that the Guild would recognize as the point of parity. While white men are paid closer to the median salary across age groups, all other groups are also closer to white men than they were before.

Overall, the pay disparity between current white newsroom employees and current newsroom employees of color who were hired under the Graham family is 12 percent. For current employees hired after Bezos acquired the newspaper, that disparity is down to 5 percent. In particular, the gender pay gap has narrowed for new hires. Whereas the disparity between men and women who were hired under the Graham era is 5 percent, that figure is down to 3 percent for current employees hired after Bezos purchased the paper. A big drop occurred between white men and women of color, down from a 16 percent disparity to an eight percent disparity.

For current employees hired under Bezos’s ownership, salaries when accounting for age (years in journalism) and median desk pay are as follows:

- White men are paid an average of 9 percent higher than the median for their age group and desk

- White women are paid an average of 6 percent higher than the median for their age group and desk

- Men of color are paid an average of 3 percent higher than the median for their age group and desk

- Women of color are paid an average of 1 percent higher than the median for their age group and desk

COMMERCIAL

Analysis of the organization’s commercial side as a whole is difficult, because it includes nine different departments across the organization and only 133 salaried employees and 147 hourly employees. These numbers are large enough for topline analysis, but with the introduction of more and more factors, the results become less reliable. In many departments, it is difficult to ascertain pay equity or disparity across races/ethnicities and genders because they have too few employees. The following section attempts to examine pay where possible. As with the newsroom section, topline numbers are only reliable insofar as they reveal broad trends, though they cannot capture other factors that influence pay, such as years of experience or the demands of the job itself.

About one-third of Guild-covered employees work on the commercial side of The Post. Overall, gender pay disparities are nearly nonexistent. For the 47 salaried men working in commercial at The Post, the median salary is $86,880; for the 86 women, it’s $85,977. The difference of 1 percent indicates that the two groups are effectively on par.

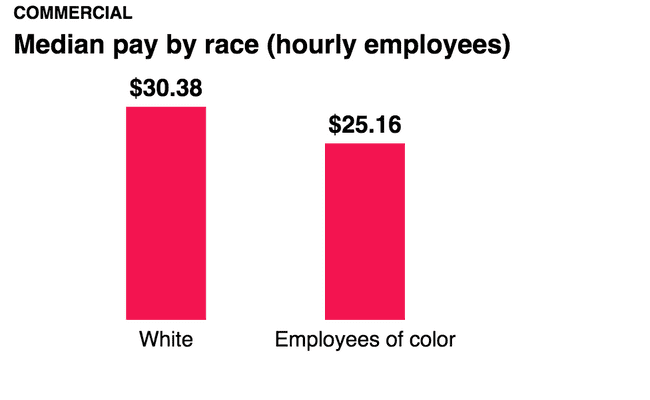

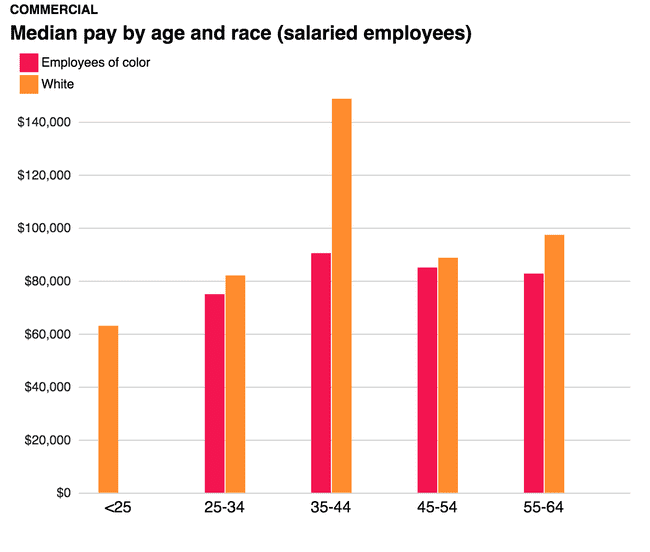

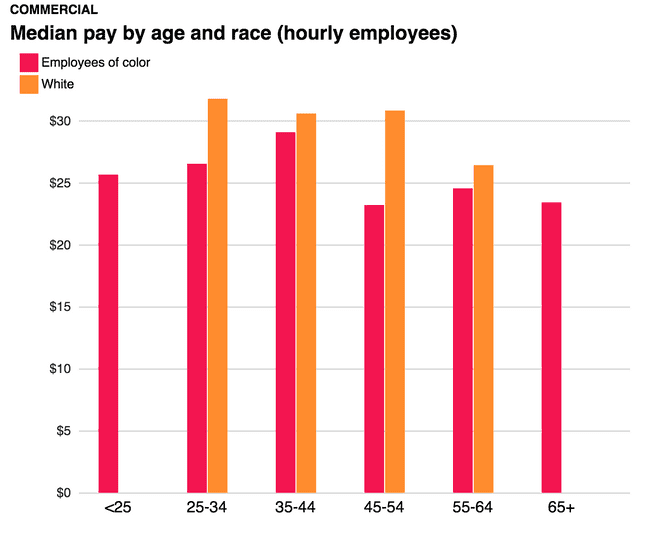

That equity does not hold when it comes to race and ethnicity, though disparities are smaller on the newsroom side. For the 99 salaried employees on the commercial side who are white, the median salary is $88,000; For the 32 employees of color working alongside them, the median salary is $83,445. That disparity of 5.5 percent is lower than the disparity for commercial’s hourly employees. For the 43 hourly employees in commercial who are white, the median hourly rate is $30.38; for the 101 employees of color working alongside them, the median hourly rate is $25.16. That represents a disparity of more than 20 percent.

When adjusting for age, the disparity grows even larger. The gap between the median ages of employees of color and white employees overall is five years; the median age for white salaried employees is 35, and for employees of color it is 40. For hourly employees, the median ages are 39 and 47, respectively. So employees of color in commercial tend to be paid less than their white counterparts, despite tending to have more experience in their jobs.

Examining race and ethnicity within genders reveals an interesting pattern. Among women, the racial pay disparity is quite low. The 67 salaried white women in commercial have a median salary that is 1.3 percent higher than that of the 17 women of color. This gap falls within the range that the Guild considers approximate pay parity. The women are clustered around the median salary for all of commercial.

But between white men and men of color, the pay disparity is stark. For the 32 white men, the median salary is $94,497; for the 15 men of color, the median salary is $76,866. That disparity is 22.9 percent, one of the highest disparities seen across the entire organization.

This trend is different for hourly employees. In many workplaces, the biggest pay gap tends to exist between white men and women of color, but in commercial, the biggest gap among hourly employees is the gap between white women and men of color. In fact, the gap between white men and women of color is almost nonexistent. The median hourly rate for the 21 white men in commercial is $26.76, compared with $26.54 for the 52 women of color — a difference of just 0.8 percent. On the other hand, the median hourly rate for 22 white women is $31.76 and for the 49 men of color is $23.33, a 36.1 percent disparity.

One of the issues with attempting to determine disparities across commercial is that the data does not allow us to determine how many hours an employee works. The data distinguishes between full- and part-time hourly employees but does not count how many hours part-time employees work (which would be difficult, because of the fluidity of many part-time schedules).

When analyzing just the full-time hourly employees in commercial, the disparities shrink and shift. For the men and women of color, the wages are virtually the same for full-time employees on an hourly wage. For white men and women, hourly wages are about $2 apart. But while full-time men and women of color have median hourly rates of $26.04 and $26.82, respectively, full-time white men and women have median hourly rates of $29.91 and $31.84, respectively.

There is a slight gender disparity in the scores that commercial employees have received on performance evaluations. While the median score for women is 3.3, the median score for men is 3.2. Similarly, when it comes to race and ethnicity, while white and Asian employees in commercial each have a median score of 3.3, black employees have a median score of 3.2 and Hispanic or Latino employees each have a median score of 3.15.

Finally, an analysis of raises for The Post’s commercial employees shows few disparities in who receives them. The most common type of raise among commercial employees, with the exception of those mandated by Guild contracts, is merit raises.

Men received 44.3 percent of those merit raises, and women received 55.7 percent. (The gender makeup of commercial is 42.9 percent male and 57.1 percent female.)

The percentages of merit raises distributed by race and ethnicity for salaried commercial employees were as follows:

- Black: 47.4 percent

- White: 40.7 percent

- Asian: 7.1 percent

- Hispanic or Latino: 3.5 percent

- All others: 1.3 percent

For contrast, over that time the racial and ethnic makeup of salaried employees was as follows:

- Black: 37.5 percent

- White: 47.8 percent

- Asian: 7.3 percent

- Hispanic or Latino: 4.2 percent

- All others: 3.1 percent

Merit raises went to these groups in the following percentages, compared to the percentages they make up in commercial:

- White men: 17.1 percent of merit raises vs. 18 percent of employees

- White women: 23.6 percent of merit raises vs. 29.8 percent of employees

- Men of color: 27.1 percent of merit raises vs. 24.9 percent of employees

- Women of color: 31.9 percent of merit raises vs. 27.3 percent of employees

ADDITIONAL ANALYSIS

The analysis provided above is a fraction of the analysis completed as part of this pay study. If we had written it all up, this report would be much, much longer. The numbers in this report represent the most relevant topline numbers in the analysis, and all attempts were made to present those numbers alongside context including factors such as age and job.

The Post Guild's full analysis is available on GitHub at https://github.com/postguild/paystudy2019.

TESTIMONIES

In interviews, employees across desks and departments described troubling pay disparities between colleagues doing the same job, even with the same level of experience. They expressed frustration with a system that encourages employees to seek offers elsewhere in order to receive significant raises. They spoke of a hiring process that benefits industry insiders coming from higher-paying competitors and that too often sets back women, people of color, and journalists from smaller publications.

The employees that the Post Guild interviewed come from a variety of departments in the newsroom, including Video, Photo, Local, Foreign, Style and Graphics, as well as from commercial. All asked for their names and certain identifying details to be withheld.

Veteran employees hired as interns or entry-level staff members described being pigeonholed into jobs with slow, incremental raises and limited opportunities for substantial salary boosts. One news reporter hired as an intern nearly 20 years ago said he still makes less than $70,000 a year. He’s thinking about getting a part-time job, he said, possibly driving for Uber.

“This is not to disparage anybody … but it’s tough to sit there and look at someone who’s 15 years younger than you, with 10, 15, 20 years less experience, making significantly more than you,” he said. “It feels like a caste system.”

One veteran reporter said it took her more than two decades at The Post to feel that she had any substantial disposable income. At one point, while working as a foreign bureau chief, she learned that the man who previously held her job, a reporter of the same age with more managerial experience but a fraction of her experience at The Post, was making $50,000 more than her.

Another female employee, a 35-year-old award-winning journalist who started as an intern in the mid-2000s, recently found out that all of the men on her team are paid more than her — even though she’s been at The Post longer than all of them and has been working in journalism longer than most of them. One of the men on her team is paid more than $30,000 more than her.

While she has received incremental raises, The Post only gave her a substantial raise after a competitor offered her a job several years ago.

“It’s always disgusted me that the only way we can get what we deserve is by getting an offer somewhere else,” she said. “How is that a way to show that you value someone?”

She has noticed a pattern of young women like her being hired at low salaries and getting “stuck.”

“We don’t know what we should be paid, because no one tells you that in college,” she said. “You take what you’re offered, and then you’re on this track.”

One 32-year-old female newsroom employee was hired about a year and a half ago after two years in journalism and about a decade of other related job experience. The Post job application asked her how much she made in her previous job, as a fellow at a nonprofit journalism outlet, and how much she would like to make in her new job.

Not long after she joined The Post, she found out that a colleague who started on the exact same day, in the same position, with a similar level of experience, was hired at a salary $14,000 higher than hers. That colleague told her that before she was hired, she had known another member of the team who encouraged her to negotiate for a higher salary. The 32-year-old employee, meanwhile, did not know that she could negotiate upward of 20 percent of her salary upfront.

She said she then went through the salary review process, which concluded that she was, compared to her colleagues and other market rates, underpaid by at least $10,000. But neither that information nor the process that furnished it guaranteed corrective measures of any kind.

In her annual review this year, she did get a sizable merit raise, which cut her pay disparity with her colleague in half. Still, she said, “it’s this continual uphill battle of just trying to get even.”

“That money should really not be used for corrective purposes,” she said of the merit raises. “It’s very hard, once you start at a lower point, to ever fully play catch-up. “Because as I’m playing catch-up, people are getting actual merit increases. There’s no — as far as I can see — clearly defined process or path for correcting these pay inequities.”

One 29-year-old female employee started at The Post more than five years ago in an entry-level job at a low salary. The role was a demotion from her former job but was described to her as a starting point with opportunity for advancement. She was quickly promoted to editing roles with demanding evening and weekend hours. While she has received raises almost every year, she recently learned that at least three colleagues on her team, at her same level, make tens of thousands of dollars more than her.

“It made me feel undervalued and made me question what I’m doing and if this is really a sustainable place to be,” she said. “Can I actually buy a house here? I don’t want to just live this kind of life forever.”

She wants to ask how she can bump up her salary, but she isn’t sure how or when to have that conversation with her supervisor.

“I’ve definitely noticed morale sinking for me,” she said.

On the commercial side, one employee in Client Solutions described a lack of opportunities for upward mobility, especially for people of color. The employee, a 40-year-old woman of color who has worked in Client Solutions for more than five years, said she has been trained to manage new departmental tasks outside of her role. But when she has expressed interest in applying for available positions, she has not been considered. Instead, she has taken on new responsibilities without a pay increase.

She would ideally like to transition to a role that is more in line with her new skills and training, but she has seen the department focus its hiring on young people fresh out of college. At her age, she said, “I’ve already accepted that that’s not an opportunity for me.”

The Post Guild also found pay disparities among newsroom aides, whose salary floors are much lower than those of other employees. One newsroom aide, a full-time staffer, was hired at a salary of less than $40,000 a year. As a recent college graduate, the aide did not negotiate for a higher salary.

“I think I was scared of them rescinding my job offer,” the aide said. “I feel so stupid for not doing it … It makes me so upset to even think about it. But I didn’t even think to negotiate or ask for more money.”

The employee has since found out that another aide, who is the same age, has a similar level of experience and was hired around the same time, makes $4,000 more. Another slightly more senior aide makes about $12,000 more.

The aide thought back to orientation day at The Post, when new employees were told they had been hired for long careers at the company. With such a low salary and an unclear path for moving up, the employee wondered how likely such a career at The Post might be.

“It just feels very almost disingenuous,” the employee said.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Guild believes that a diverse, equitable and inclusive workplace is key to The Post’s success as an organization. While the company has made progress, there is still work to do. To help promote such an environment, the Guild offers the following recommendations:

The Post should strengthen and better formalize the salary review process. This process — which the Guild negotiated for in its last contract — is intended as a mechanism to empower employees to understand how much they are being paid in relation to their co-workers, ideally providing the groundwork for salary negotiation conversations with their direct managers. Currently, only one Post employee conducts salary reviews for the entire company. We believe this is too much work for just one person, and we recommend that more Post employees be trained on the salary review process to ensure reviews are completed in a reasonable time frame. Furthermore, it should be made clear in new employee onboarding and orientation that employees may request a salary review at any time. We also recommend that the organization conduct salary reviews for all employees hired in the past five years. Employees who go through the salary review process should also have the option of having a Guild representative present during the process if they wish. We believe these enhancements to the salary review process can be accomplished in a reasonable time frame and would signal that the company values empowering its employees to have these conversations.

The Post should allow direct managers to know how much their reports make. Currently, many direct managers do not know this information, despite being in the best position to negotiate raises on their reports’ behalf. Also, these managers are often responsible for having salary conversations with new hires and should be appropriately informed about pay expectations. This would empower direct managers to look out for and be aware of pay disparities on their teams and help correct them, taking some of that burden off top management.

The Post should ensure that pay disparities do not begin during the hiring process. The Post currently requires prospective applicants to list their salary history and desired salary during the application process. We believe the company should remove these questions — that of previous salary history and desired salary — entirely from the application and interview process. These questions often serve to perpetuate gender pay gaps, and have already been banned from states such as California and cities such as New York. The company should not use these questions as a proxy to determine applicants’ starting salaries. As one of the largest and best-resourced newsrooms in the nation, The Post clearly has enough information to determine what the expected salary for a Post-caliber position should be.

The Post also should re-evaluate the existing two-year intern program. For many years, The Post would hire summer interns into full-time positions but classify them as “two-year interns.” Two-year interns are essentially full-time Guild-covered employees with benefits but are slotted into a salary of less than $50,000 for two years. Once they “graduate” from the two-year program, these employees are at a disadvantage with regard to pay in comparison to their peers, despite often having the same amount of experience. The Post has moved away from this model in recent years, instead hiring some interns as contractors and some as full-time staffers. Many contractors eventually transition to full-time staff, but the two-year intern classification has not been eradicated. While we applaud The Post for hiring interns and giving young people opportunities, we believe this classification, if no longer being used, should be retired entirely.

The Post must do more to ensure that the company reflects the diversity of American society. The Post must do more to recruit and retain employees from underrepresented backgrounds, especially black and Hispanic or Latino journalists. We recommend that The Post create a new job position for a recruiter to scout talent from underrepresented backgrounds. The Post should be present and actively recruiting at journalism conferences, such as those held by the National Association of Black Journalists, the Asian American Journalists Association, the National Association of Hispanic Journalists and the Native American Journalists Association. We are inspired by the recent news that Vox Media has committed to ensuring that 40 percent of applicants who pass a phone interview round must be from underrepresented backgrounds — a stipulation negotiated by the Vox Media Union. We recommend The Post adopt a similar approach and support having diverse candidate pools for positions, as an investment in our belief that diverse, representative institutions — especially in the journalism industry — better serve their communities.

To hold the company accountable in creating an equitable and diverse workplace, we also recommend that The Post hire an equity, diversity and inclusion chair/consultant and form a diversity committee. This consultant should be hired by the end of 2020. The committee should be created as soon as possible. This consultant can help the company establish goal posts for creating a more diverse workplace, draft initiatives to support these endeavors and also act as an accountability arm. The diversity committee would work closely with this consultant, but would also create and enact initiatives that support increased equity, diversity, and inclusion throughout The Post. One such project could be creating guidelines for inclusive journalism, similar to a guide published by the Seattle Times diversity committee. This committee should be made of a mix of employees from all parts of the organization.

The Post should hire a third-party consultant to conduct an annual pay study and share the results with Post employees, along with any recommended changes. This pay study should include every employee, not just Guild-covered workers, to provide the most comprehensive picture of pay within the organization.

PAY HISTORY AT THE POST

The fight for equal pay at The Washington Post has spanned decades of hard work, collective action and uncommon courage from past generations of Post employees.

When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed the Senate after the longest debate in its history, Title VII came into law, prohibiting employment discrimination based on race, sex, color, religion and national origin. The act not only prohibited discriminatory pay, but also discrimination in recruitment, hiring, assignment, promotions, benefits, discipline and layoffs.

It also created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a committee tasked with eliminating employment discrimination. It was not until 1972, however, that the EEOC gained enforcement powers, unleashing a decade of legal fights for equal employment and pay, including at The Post.

In 1972, 117 female employees of The Post joined the Washington-Baltimore Newspaper Guild to file a sex discrimination suit against The Post with the EEOC. Women at The Post had seen little improvement in their pay and working conditions since signing a memorandum of understanding with management two years earlier, in 1970. The suit was finally settled in 1980 with $50 to $250 in back pay distributed to 567 women and the company’s agreement to a five-year affirmative action plan that guaranteed one-third of editorial and commercial jobs would be filled by women.

The settlement did not require the company to admit sex discrimination or a violation of Title VII — though the EEOC in 1974 had found “reasonable cause to believe” that The Post discriminated against women in salaries, promotions, and aspects of hiring.

Not everyone was thrilled with this settlement. “If this is a victory, I’d hate to see a defeat,” one female assistant managing editor told a Post reporter in 1980.

In the same year as the 1972 sex discrimination suit, black Post employees were also organizing. Nine black reporters delivered a list of 20 pointed questions to editor Ben Bradlee about the lack of black editors and reporters, particularly on prestigious desks, and the nature of their assignments. In her memoir, Dorothy Butler Gilliam relates how one of the petitioners, LaBarbara “Bobbi” Bowman, described meetings with the editor: “His hands were shaking, and I thought, ‘We have scared Ben Bradlee.’”

Seven of the original group went on to file a complaint with the EEOC about discriminatory hiring and promotion of black reporters in a city that was then over 70 percent black. They were all junior reporters, and would come to be known as the Metro Seven. The EEOC found that the group had grounds to go to court — but they lacked the resources to do so, and so never filed a lawsuit.

Despite this, Gilliam writes, the Metro Seven’s work “did cause movement inside The Washington Post newsroom. Managers broadened subject beats, increased the number of columnists of color, and stepped up promotion and hiring” of black employees.

“The progress in hiring Blacks in daily newspapers,” Gilliam writes, “was not simply due to the largesse of white editors.”

Katharine Graham herself noted in her autobiography, “Personal History,” that “without the suits and without the laws adopted by the country,” The Post would not have seen the significant improvements it did to the numbers and working conditions of women and people of color at The Post in the 1970s.

But the story did not end there.

In the 1980s, The Post still had a pay gap problem, and the lawsuits kept coming. A new “dual” pay system instituted by management in the 1979 contract led to widening pay gaps, lower minimum salaries, and more managerial discretion in the setting of salaries and merit increases, particularly in the newsroom.

Post management argued that experience and years spent at The Post could account for pay disparity — a position it maintained as recently as 2016 — but a 1986 pay study by the Guild showed that “in the newsroom, where management has the most flexibility in setting pay, long service at the Post and experience count less for women and blacks than for white males, who often command higher salaries even with less experience and fewer years’ service.” Among reporters in 1986, the average salary for white men was $988.68 per week. For black women, it was $791.33.

One year later in 1987, Gwen Ifill wrote in a Post Guild bulletin that “The patterns for pay discrimination that have contributed over the years to low morale and wide gaps in the amount Washington Post managers are willing to pay their employees not only persist, but have widened significantly” for women and black people since 1986. White men were then earning $240.59 a week more than black women, a gap that had widened by $43.24 from the year before. “We can’t eat prestige,” Ifill wrote.

In the years since Ifill’s bulletin, pay disparities have contracted and expanded, but never closed completely. In 1988, the Guild filed a charge of discrimination with the D.C. Office of Human Rights and the EEOC. The suit was settled in 1997 with an agreement to provide final and binding arbitration by employees asserting a claim of discrimination. Eighteen such claims were filed, with the last one settled in 2003.

The Guild conducted a pay study at The Post in 2016 that revealed significant disparities, although Post management dismissed the results and declined the Guild’s invitation to address the issue collaboratively. However, the Guild’s persistence in 2017-2018 contract negotiations resulted in a new contract section: Article XVIII(c), which empowered employees to initiate individual pay equity reviews conducted by the Human Resources department.

The advancements made by previous generations of Post employees, empowered by civil rights legislation and by the Guild, are a testament to the power of collective action and the bravery of those who put their jobs on the line in the name of equality. As the latest pay study will attest, there is still much work to be done.

PAY STUDIES AT OTHER COMPANIES

The Post Guild, of course, is not the only entity to conduct a pay study. Google and Citigroup are two major companies that have recently conducted public pay equity studies.

In March 2019, Google released a summary of its 2018 pay analysis only for groups consisting of 30 employees or more, containing five or more people per demographic (i.e. women, men, minority, non-minority) to ensure statistical accuracy. Google says the purpose was to “identify any unexplained differences between groups of Googlers who are doing the same job.” Google found in one particular job code, men received less discretionary funds than women, but did not elaborate on any other job code discrepancies. Google spent $9.7 million on pay gap adjustments across 10,677 employees, 49 percent of which was spent correcting hire offers. The company was critiqued for examining only if demographic groups were being paid equally for the same job, rather than addressing which jobs and pay groups certain demographic groups are placed into.

The Citigroup study, released January 2018, differentiated between “adjusted” pay gaps, which account for “job function, level and geography,” and unadjusted, or raw, pay gaps. The adjusted analysis found negligible disparities between women and men, and between minorities and non-minorities. But the raw data showed that the median pay for women globally was 71 percent of the median for men, and that the median pay for U.S. minorities was 93 percent of the median for non-minorities. Citigroup resolved to increase representation of women and minorities in managerial levels.

A number of media unions have also conducted their own pay studies of their newsrooms, such as Bloomberg. Published in January 2019, the study found that Bloomberg BNA has a newer workforce (more than half of the bargaining unit employees having less than five years at the company) and is above average in terms of gender diversity compared to the news industry. Still, the study concluded that significant pay disparities exist. The median salary for black employees is on average $7,800 less than their white counterparts. For Hispanic employees, on average $10,609 less than their white counterparts. Pay disparities appeared to be widening for newly hired women into the commercial and IT departments. Across the board, women make less than their male counterparts and employees of color make less than their white counterparts. It’s also worth noting that white employees were found to be overrepresented in the newsroom.

While Bloomberg has made an effort to bring in new hires, the merit pay system already in place meant the pay disparities inevitably continued, and the company does not have a mechanism to balance pay. The study recommended a proactive pay policy for new hires and compensation for current employees. BBNA’s guild chair noted that she found the methodology flawed because it is difficult to quantify experience. She also noted that disparities varied across groups in the company, and that that should be kept in mind as solutions are proposed.

METHODOLOGY

The Washington Post Newspaper Guild received pay data from Post management on July 2, 2019, after Alice Li and Sophie Ho, co-chairs of the Guild Diversity and Equity Committee, made a request pursuant to the Guild’s contract with The Post. On that date, data was transmitted to the Washington-Baltimore News Guild via a thumb drive, which was transferred to Steven Rich. Data was transferred to an air-gapped machine — one that wasn’t connected to the Internet — and the thumb drive was returned to the News Guild. Rich was the only member of the Post Guild granted access to the data, and data was promptly destroyed upon completion of the analysis to prevent the full data set from becoming public.

The data comprised two Microsoft Excel spreadsheets with three tabs each: one spreadsheet for The Post’s current Guild-covered employees and one spreadsheet for terminated employees, as of July 2. This only includes employees who were covered by the union’s collective bargaining agreement with The Post, regardless of whether they are dues-paying members of the Guild, and is not a complete survey of salaries across the organization; it is unclear how many Post employees, such as managers, are excluded. The data lists 950 current employees and 539 terminated employees. Here, “terminated” means terminated from the Guild, which in most cases means that the employee left The Post, but can also mean that the employee was promoted to a position ineligible for Guild membership.

The first tab of the data contains 167 fields of information about each current employee and 128 for employees who left or are no longer covered by the Guild. (Only one field in the latter doesn’t appear in the former: date of termination.) This provides a fairly comprehensive look at employees at The Post, excluding one field that the Guild is not entitled to: full legal name of the employee. It would be feasible to determine some names using the available information, but the Guild made no attempt to identify anyone in the data and, over the course of its analysis, never perused the records of individual employees.

Identifying the median salaries of small numbers of people would make it easy to discern individuals’ salaries, so the Guild took two preventive measures, while also aiming to accumulate as many accurate results as possible. The first involved grouping employees by factors such as age, race and newsroom desk. The Guild created these groups in consultation with experts who study pay trends as well as Guild members familiar with the newsroom’s structure. Second, we suppressed results from any group or subgroup that had fewer than five people, because results for small groups can be misleading. For example, in a group of three people, the person who makes the second-largest or second-smallest amount of money has the median salary. Additionally, all three members would know exactly who they are in the analysis, an outcome that seemed preferable to avoid.

To study salaries by gender, the Guild relied on a field provided by The Post. The field is binary, containing no additional information beyond “male” or “female.” It is unclear how The Post determined this information for its employees. That caveat aside, the field had information for every employee in the data set.

Analysis in Python was written by Steven Rich and audited by Aaron Williams. Analysis in R was written by Steven Rich and audited by Andrew Ba Tran.

CONTRIBUTORS

Jacob Brogan, assistant editor

Helen Carefoot, editorial aide

Hau Chu, Post Guild secretary, editorial aide

Jessica Contrera, staff writer

Dave DeJesus, Post Guild co-chair for commercial, client solutions

Rick Ehrmann, Post Guild representative

Armand Emamdjomeh, graphics reporter

Joe Fox, graphics reporter

Sophie Ho, Post Guild co-chair for Equity and Diversity Committee, audience analyst

Pat Jacob, Post Guild vice chair for commercial, account executive

Hannah Jewell, video reporter

Sarah Kaplan, Post Guild chief steward, staff writer

Fredrick Kunkle, Post Guild chair emeritus, staff writer

Marissa Lang, staff writer

Joyce Lee, video editor

Alice Li, Post Guild co-chair for Equity and Diversity Committee, video reporter

Katie Mettler, Post Guild co-chair for news, staff writer

Justin Moyer, Post Guild vice chair for news, staff writer

Razzan Nakhlawi, social media producer

Sophia Nguyen, staff writer

Lynn Olson, Post Guild vice chair for nightside, assistant editor

Steven Rich, data editor

Tonya Riley, research assistant

Ric Sanchez, social media producer

Samantha Schmidt, staff writer

Matt Schnabel, multiplatform editor

Andrew Ba Tran, data reporter

Aaron Williams, data reporter

Jamie Zega, multiplatform editor